I’m so excited to begin this series profiling artists who also write, writers who also paint, and what it means to be working in both the written and visual. (If you are one of these creatives with a foot in both worlds, drop us a line!) The first artist in this series is Joanna Streetly, who lives, most wonderfully, on a floating home off of Vancouver Island. Read about her life, her remarkable mother, and the sources of her inspiration, and see if you don’t find yourself longing to get rid of your possessions and live the challenging, glorious life of an artist in a floating world:

Rachel-Who inspired you as a child and made creative pursuits a possibility for you? How did you begin?

Joanna-I grew up with a desperately artistic mother who was formally trained in England and painted her way through WWII while also working as an aircraft engineer for the WRENS. When she met my father she was a single mother to my oldest sister, teaching art in Washington DC, and had been on the brink of moving to an artists’ commune in Mexico. Instead, they moved to the remote sugar cane fields of Trinidad. I was the fifth of five children and my mother was 46 when I was born—tired and ill—yet her relentless drive to create meant she kept busy with commissions. I remember her giving me charcoal or pastels and paper and always advising me to stand far back to assess my work. As a teenager I attended life drawing classes with her. She was fiercely critical and never gave false praise. At the time I found this demoralizing, but I now see it as a sign of her uncompromising dedication to improvement and integrity. Mum’s honesty help to thicken my skin in preparation for a career in writing where feedback, (invited and uninvited,) dominates and has the potential to devastate sensitive writers.

Artist: Elizabeth Streetly

Rachel-Did you start out in painting or in writing? When did you realize that one would be your primary creative passion?

Joanna-Perhaps artistic ability is genetic or maybe it developed through exposure to my mother’s work, but I was a quick study and I remember spending hours drawing horses and faces when I was quite young. When I was nine we left our home in Iere Village and moved to Port of Spain, the capital city of Trinidad. At the time I wrote an essay about the loss of my beloved childhood home and it received a lot of attention. This was when the written word began to call me in ways that felt both necessary and rewarding. The more I wrote, the more I chose writing as my primary form of self-expression. And while I found visual art rewarding, and have moonlighted as a designer and illustrator, I think I’ve also viewed visual art as something I can come back to at any point; whereas writing is a career that requires me to constantly nurture and accrete the layers of development. The brain/keyboard relationship feels more demanding than the eye/hand relationship and I am continually reaching for ways to ensure my writing achieves its potential. It’s this process of growth that draws me.

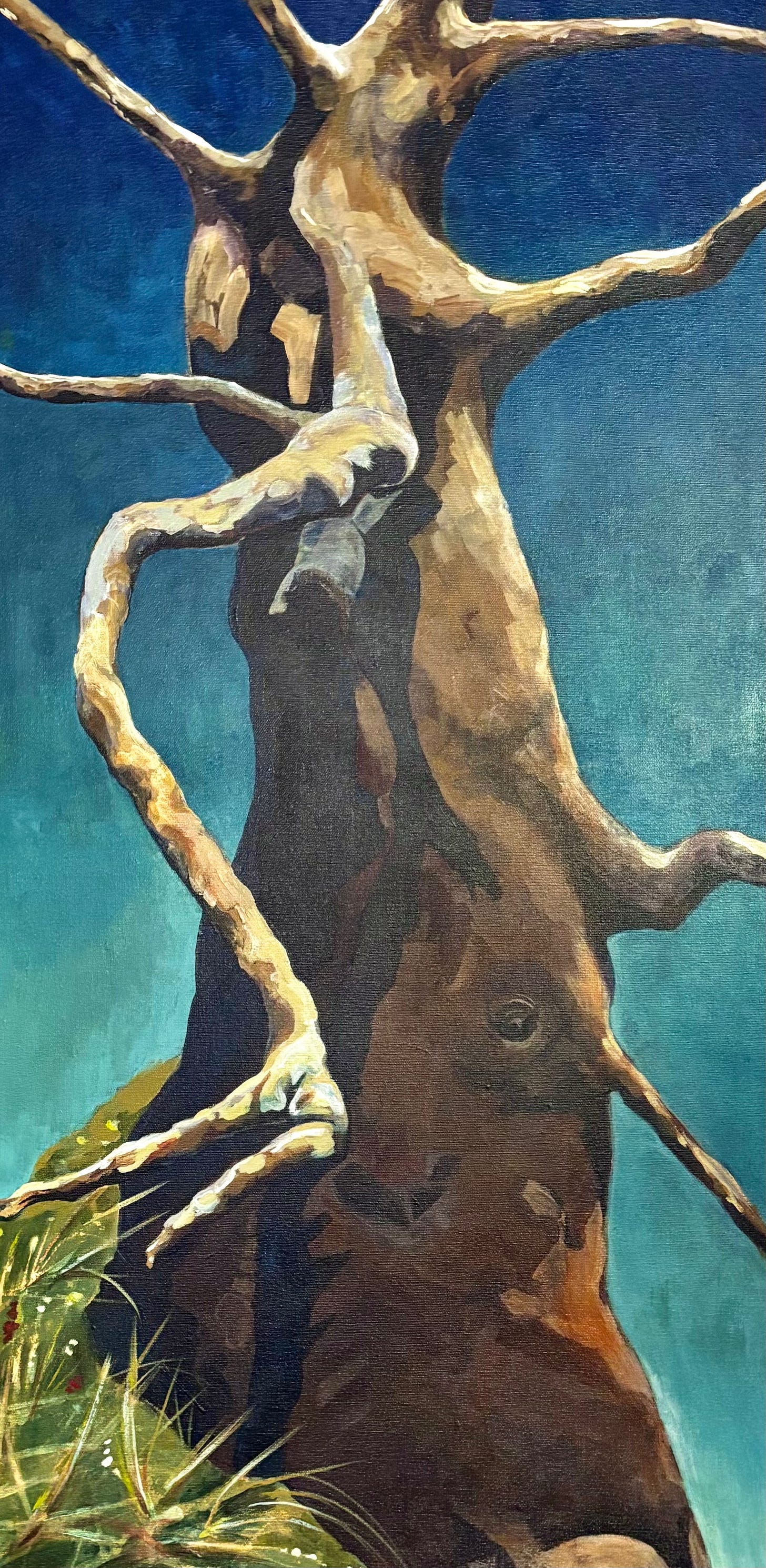

Joanna Streetly—“Spruce on the Edge”

Rachel-Is art currently you full time job? If so, how does your income break down (gallery shows, studio work, teaching, etc.)? If not full time, what’s your side hustle/how do you make ends meet? Does your other work encourage your creative interest and ability or is it entirely separate?

Joanna-The need to pay rent forces artists to take paths that are antithetical to artistic flow and practise. I learned this when I first started out as a freelance writer after publishing my first book in 2000 when the Internet was just fledging. Money was so sporadic. Some magazines paid on acceptance, some on publication, some didn’t pay at all! I remember checking my mailbox daily and rushing to the bank with those precious envelopes.

I buffered this by taking a two-day-a-week job in the admitting department at the hospital. I’ve kept that job (and its benefits package) for twenty plus years, and I still love the way I can walk out of the door at the end of a shift and leave it all behind. But two days a week in a hospital doesn’t pay the rent in Tofino. In 1995 I built a float house and anchored it in Clayoquot Sound, so I could forgo rent. I didn’t have electricity or running water and I had to travel by boat, but I didn’t care. I loved this way of life. I also had to stop oil painting because I just couldn’t share such a small space with the fumes. (The need for a separate studio has been a key barrier to furthering my career as a visual artist, although I have done a lot of work as a pen-and-ink illustrator.) Beyond the issue of space, I’ve learned to retrain my writing habits and prioritize work that has money attached to it. I take substantive editing contracts and teach memoir and poetry workshops when they come up. I’ve had several large grants that have allowed me to write fiction; I choose publications that pay and I avoid embarking on big projects that have to be sent out on spec. Of course, none of this applies to poetry. When I write poetry I revel in the absolute indulgence of it. It’s the pinnacle of all creative practises, with the measliest of incomes.

Rachel-Do you have formal arts education? Do you feel that your formal education was necessary for your career?

Joanna-I decided against studying English Literature at university because I didn’t want to spend my life picking apart the work of other people—I wanted to create the work myself! But in 1987, creative writing wasn’t offered at universities in England. In an adolescent about-face, I moved to Canada to study outdoor education instead. Lately, I’ve wished I had an MFA in creative writing. But fellow writers who’ve taken that MFA have counselled against it, citing my experience as a published author and editor and advising that it’s expensive and unnecessary. Maybe if I were more financially stable I would consider it. In terms of skills development, the six-week creative writing programs through Orion Magazine have been a huge turn-on for me. They are always taught by professionals and appeal to my interest in landscape, eco-poetry and the Anthropocene. I also took a substantive editing course through SFU which has been very useful. For now an MFA is a luxury I can’t afford, but I still sort-of want it. Go figure.

Rachel-What are you working on now that you are most excited about?

Currently I’m at work on a novel, but I’m most excited about developing video and audio versions of poems from my forthcoming collection, All of Us Hidden, (Caitlin Press, September, 2025). I love dramatic recordings of poetry and I’m always looking for ways to introduce new dimensions to my work.

~ ~ ~

Thank you, Joanna, for the inspiration, and for showing Desperate Artists and Writers how it can be done—with difficulty, with struggles, but also with freedom, beauty and integrity.

Joanna Streetly is the published author of five books. Her work can be found in in Best Canadian Essays 2017 and Best Canadian Poetry 2024, as well as many anthologies and literary magazines. She is the winner of the FBCW Literary Writes poetry competition and has been short-listed for the The Spectator’s Shiva Naipaul award for outstanding travel writing and long listed for the Canada Writes Creative Non-fiction Prize. She has lived in the unceded territory of the Tla-o-qui-aht for over thirty years and was the inaugural Tofino Poet Laureate. Her new poetry collection, All of Us Hidden, will be published by Caitlin Press this summer.

Here is an excerpt from “Letting Go”

(Original version published by Key Porter in Between Interruptions: 30 Women Tell the Truth About Motherhood, edited by Cori Howard. Later published by Caitlin Press in Wild Fierce Life: Dangerous Moments on the Outer Coast.)

When my daughter Toby was old enough to sit up, we began to visit a small islet we called Cathie’s rock. The grassy knoll was a vantage point from which to see our world, (home, channel, island). But the islet offered something else, an eagle feather dangling from a weathered tripod of sticks. The feather was important, the part of learning which included people and history.

Before I lived in Maltby Slough, the bay was home to Mike and Cathie and their daughter April. They were role models to me in the ways of wilderness living. But when April was ten, Cathie began treatment for leukaemia. And before April was twelve, Cathie died. For some time we’d been communicating only by letter as her strength ebbed. Her love of nature sustained her and she wrote of spring sweeping over the mudflats, the blossoming of salmonberry flowers and the arrival of Rufous hummingbirds. She’d begun to meditate, hanging an eagle feather at a small grassy island.

By now, the simple sticks had weathered to grey and the feather was stripped of lustre by the unstoppable winter winds. But even so, as it bobbed and turned in the air, it captured our full attention—Toby reaching out to it with both hands. Before having a baby, when I’d come to the feather, I’d dedicated myself to thoughts of Cathie. I remembered her observations of nature and shared my own. I pictured her shy smile and told her I missed her.

But sitting there with a baby in my lap I saw a new and bitter sorrow in Cathie’s death, that of a mother parting from her child. The fluttering feather spoke of impermanence, the lack of certainty in life. I was pierced by the reality of leaving behind a child, the unfinished business of parenting. With time, even the best memories fade. What if my child went through life not knowing how greatly I loved her? I tightened my hold on Toby and thought about my father’s death five years earlier. His importance to me was something I could only tell her about, nothing she could feel or know for herself. What if I, like Cathie, had to rely on someone else to tell Toby about me? Would I like their choice of words? Would they remember my successes without mentioning my failures? What if they described me only as a writer? What about all the other parts of me? The concept of letting go seemed exquisitely painful once a child was involved.

I wondered, suddenly, about my own mother. She didn’t speak about herself much. Did I know enough about her? I knew that when I was two, she went alone into the Pacaraima mountains of Guyana. A missionary walked her to the remote Amerindian village of Kurukubaru and left her there, returning for her three weeks later. Her paintings from that time in Guyana are of cloud-shadowed blue hillscapes, women, children and scenes of Amerindian village life. The paintings convey her love of landscape and interest in people, but they don’t tell the story of a woman torn between art and adventure on one hand, and a brood of five children on the other. I imagine the emancipation she must have felt while painting—the hunger to make up for lost time. How many other stories was I missing out on? How lacking was my sense of her? As my mother aged, now entering her eighties, the unique and wild experiences of her life were coalescing, gathering into an essence she would take with her when she died.

Here is a link to Joanna’s forthcoming book:

https://caitlinpress.com/Books/A/All-of-Us-Hidden

What a creative force is this writer/poet/artist Joanna Streetly! She proves all one really needs is the urge to share one's visions with the world. Of course, it was difficult for her mother with five(!) young 'uns scrambling for her attention (that portrait by Elizabeth is stunning!), but she still seemed to make time for herself to honour the desire to create. Looks like Joanna was watching closely. Wonderful first interview in this series.

Rachel! This first-in-the-series makes me look so forward to more, too. Because this is SO so good. To read about the real life of a writer/artist, with a two day/week job, and the odd grant, and Oh!! the memories of flying to the mailbox with hope! How it was. The need to prioritize one work over another to sustain.

There was a time when an MFA was very writing-focused. Having taught in a program, and studied in another, I can say many now favour an academic approach. If you have a solid writing group, you have what you would in a program. I understand the drive, though. I'm currently taking courses in theology and keep wondering if I should "just do a degree." Then wonder if I'll enjoy it as much; as it is, I take the full length of time to fulfill one at a time course--nine months--and read thoroughly "outside" the reading list--which is how I wanted to study when I was a student... back when I opted for a history degree over English, for much the same reason as Joanna, and because story ideas visited me in history class, not English.

Congratulations, Joanna, on carving out and prioritizing a true artist's life! No easy thing!